Analyzing the Effectiveness of Curriculum Implementation at the Ground Level

Decentering the Big Picture: Moving from Theory to Practice

Figure 1. Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2005)

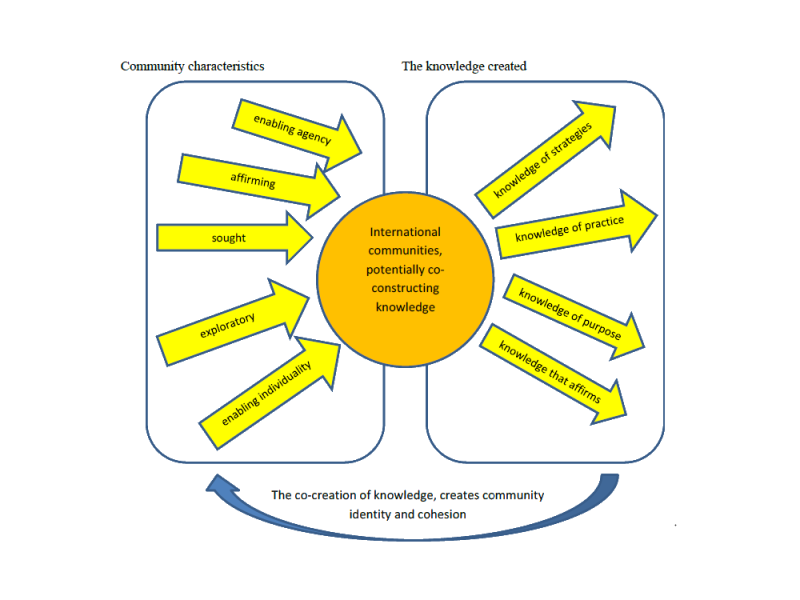

Figure 2. Types of knowledge generated within extended communities of teachers (Underwood, 2017)

Video Clip 1. This video focuses on the relevance of Bronfenbrenner's and Underwood's theories to the successful implementation of Te Whāriki, with particular emphasis on the role of the teacher as the most important person in the curriculum implementation process.

Supporting Teachers’ Competencies

Figure 3. Lack of competent bicultural teachers.

Research evidence suggested that more support is needed to be given to a significant proportion of teachers from non-Māori backgrounds facing challenges of implementing the bicultural expectations of Te Whāriki (Education Review Office, 2018, 2019). In a series of studies (Taniwha, 2010; Ritchie & Rau, 2006; Jenkin, 2009; Harvey, 2015; Ritchie, 2016; Smits, 2019; Chan, 2011, 2019 ; Jenkin, 2017; Holder, 2016), most practices observed reflect a superficial bicultural approach and is often perceived as “lip service to this bicultural commitment” (Williams et al., 2012, p. 38). This reveals that teachers are not equipped with enough Māori content and overall tools to sustain themselves as competent bicultural teachers in which Meade (2011) proposed that the knowledgeable Māori teachers could support teachers from non-Māori backgrounds in the pursuit of bicultural competence and confidence through the sharing of existing professional knowledge within professional learning communities of teachers.

Figure 4. Lack of qualified teachers.

Although the government is expecting to incentivize more teacher-led services to operate with a fully qualified workforce (Collins, 2020), this does not solve the current problem - the need to train and develop the huge numbers of untrained and under-qualified teachers who are already in post. The required percentage of qualified and certified teachers remains at 50 percent in teacher-led services (Ministry of Education, 2020). This particularly worrying as it suggests that five teachers qualified out of ten provide sufficient guarantees in terms of quality which is no doubt untrue because studies have shown that teacher quality relate to school quality and to children's success (Manning et al., 2017; Meade et al., 2012).

Although teacher qualifications leads to improvements in quality of implementation (Jenkin, 2016), Khalid, Kalsoom, and Aziz (2019) argues that it is knowledge sharing among teachers rather than qualifications which is likely to build capability and a shared understanding in the implementation of Te Whāriki. It is within professional learning communities that predominantly teachers will have access to useful guidance to develop awareness and confidence in their ability to implement Te Whāriki locally at the microsystem level and also for channeling information to the next wider community of teachers at the exosystem level (Sancho-Gil & Domingo-Coscollola, 2019). This has been framed with the idea that non-positional teacher leadership contributes to teacher agency for curriculum implementation (Frost, 2017).

Lack of Clarity Around Children's Learning

Figure 5. Inconsistent delivery and teaching of curricular content.

Because Te Whāriki does not specify outcomes and practices, services and teacher's interpretations of Te Whāriki can be assumed to vary widely, which in turn leads to inconsistent practice in the delivery and teaching of curricular content. Some recent research shows that a large amount of funding was given to undertake a study to better document what children are learning in the Early Childhood Education and Care sector, but it is not conclusive (Blaiklock, 2013).

Figure 6. Judgments about the legitimacy and credibility of a particular teacher's assessment of their child's performance.

Another problem is the lack of clarity, consistency and guidance in the use of Learning Stories as the main form of assessment for children's learning. The investigations carried out by Mitchell et al. (2011), Salcin-Watts (2019), Smith (2011), and Zhang (2017) have revealed many other concerns about the use of Learning Stories and its credibility in showing progress and achievement in children’s learning over time. Although there is little evidence about the effectiveness of the widespread use of Learning Stories to assess and enhance children’s learning (FitzGerald, 2016; Blaiklock, 2018), the developers of the Te Whāriki did not consider the possibility of replacing it with a more accurate assessment method. Unsurprisingly, the development of Learning Stories was led by Dr Margaret Carr, the same person who had co-developed Te Whāriki, which might underpin a refusal to recognize the flaws and inadequacies on her own work.

Both these criticisms may suggest that teachers were not fully committed to in-depth professional learning, which resulted in uncertainty, confusion and mixed understandings of curriculum and assessment within Te Whāriki. In an effort to establish a basis for developing the professional knowledge base expected of teachers, the combination of Bronfenbrenner's (2005) and Underwood's (2017) theories sheds light on professional learning communities at the exosystem level which was perceived to support non-positional teacher leadership in building a shared understanding of the national curriculum model and enable a greater focus and clarity when implementing local curriculum (Netolicky, 2016; Frost, 2017).

The Crisis of Professional Knowledge

Figure 7. What processes promote teacher retention?

There is the startling fact of how teacher turnover rates have ranged between 19.4% and 25.6% since 2005 to 2013, and is higher than the national workforce turnover rate (Ministry of Education, 2014). Even though the most recent comprehensive survey of teacher turnover in licensed Early Childhood Education and Care services in New Zealand was undertaken more than five years ago, which could undermine the accuracy of the findings in relation to the current teacher turnover rate, this does not alter the fact that the recent Covid-19 crisis has put a spotlight on the lack of qualified teachers and the relatively low retention of more experienced teachers within the early childhood sector (Walters, 2020). This highlighted a significant loss in terms of vital professional knowledge at some point of the process that Garcia and Weiss (2019) found necessary to create professional learning communities that helps facilitate recruitment and retention while at the same time ensuring knowledge continuity for all children have competent and qualified teachers.

Figure 8. Tapping immigrant teachers to help.

During this time, schools are also actively recruiting and relying on immigrant teachers to solve the teacher shortage issue and the proportion of migrant teachers is very high, particularly those who cannot speak te reo Māori or Pasifika languages (Arndt, 2015, 2016), and this fact cast doubts on the ability of immigrant teachers to carry out the required tasks to meet the bicultural, bilingual intent of the curriculum (Rana, 2020; Arndt, 2016). To ensure that immigrant teachers are skilled and confident to support a fuller implementation of Te Whāriki, research by Urie Bronfenbrenner (2005) and Underwood (2017) established the need for schools to develop a professional learning community at the level of the exosystem, that encompass a range of cultures, professional backgrounds and expertise across New Zealand. Borrowing the idea of teacher leadership from Frost (2017), the effort should be conscientiously made to mobilize teacher agency in professional learning communities for curriculum implementation.

Conclusion

Video Clip 2. This video concludes by reinforcing the need to create a professional community of teachers as a key solution to the issues related to curriculum implementation and gets readers thinking about the sustainability of a professional learning community.